A Case For Ethics

Written by Timothy Berggren.

Scenario 1: I sit at my desk, frantically clicking my pen, nervously calculating the odds that I’m going to get out unscathed. It’s March 2014, I’m now 26 years old working at Wells Fargo as an account manager. My boss has just told me that I have been underperforming compared to my colleagues and it’s bringing the whole branch’s performance down. He says that he’s up for a big bonus this quarter if the branch meets performance benchmarks and I’m holding everyone back. It was clear I had two choices: cheat and boost performance or do honest work and lose my job.

Scenario 2: I sit at my desk, frantically swiveling in my chair, wondering how I’m going to pass this upcoming midterm. Spring break was a bit too much fun and now I’m behind on my schoolwork. My 1,000 other commitments are getting in the way and I’m stressed out that I’m not stressed out enough. The midterm is tomorrow morning at 8 am and I’ve been pretending to study for the past three hours. It’s 20% of my grade and if I want to get an MBA at a top school, I NEED to pass. It was clear I only had two choices: cheat and get the grade or try to learn the material and do poorly.

Every day we are faced with ethical dilemmas. For most of us, making the right choice has become part of our routine. You see a wallet left behind on a table in the Haas courtyard – you will probably turn it into the lost and found or find out who owns it and look them up on Facebook to return it. You see a friends’ significant other cheating on your friend, you will probably take a picture (pics or it didn’t happen) and save your friend from a bad relationship. You probably won’t steal money from your roommate, or lie on your resume, or punch someone on your way to school today. These choices exist but our habits and routines that are reinforced by social constructs make them seem ridiculous and impossible.

So how does someone who ALWAYS makes the right choices act in a situation where it’s their job and their family’s livelihood on the line? What if that person does the right thing MOST of the time? Or SOME of the time? Are they less likely to make the right choice? When things aren’t so black and white, it’s important to have some type of moral grounding to stand on.

There’s something called the broken window theory. Imagine an old abandoned manufacturing warehouse made of brick with giant windows lining the second story. If the windows are all intact, you are less likely to throw a rock and be the first one to break a window. If there are lots of holes in the windows and graffiti, you are far more likely to throw a rock at the windows. The idea is that small bad choices compound into bigger and worse choices and can eventually lead to a catastrophe (someone burns down the building).

Wells Fargo was the building and the people throwing rocks were employees of the company. It took a couple managers to throw the first couple rocks and then it became okay for the account managers to throw more rocks. More and more rocks were thrown until the building came down and Wells Fargo finally lost the trust of the public.

Prof. Alan Ross, who teaches UGBA 107 (Business Ethics), teaches students some ethical frameworks to help understand where our morals come from and why we make the choices we do. We are confronted with some ethical dilemmas and taught to argue how we might act from one framework to another. This helps us to understand that there is never one right answer, but that it’s more about how that decision is backed up with support.

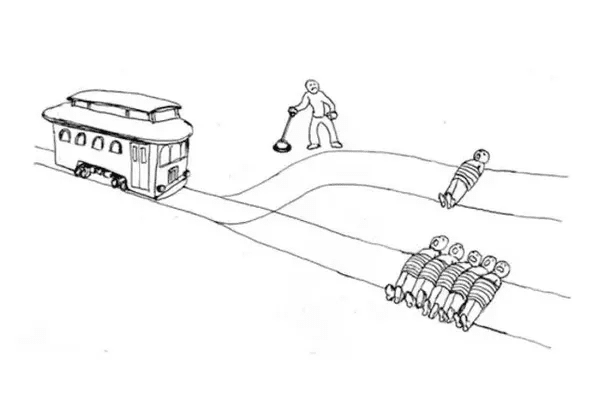

The classic ethical dilemma is the one where a train is about to run over five people, but you have the choice to switch the tracks so that the train only runs over one person. What do you do? There really is no one right answer because, either way, it ends in tragedy.

The point of the exercise is to practice our critical thinking skills and to examine our moral ground. When something questions our moral ground, how we react either reinforces good habits or creates bad habits. Haas has a unique ecosystem that helps to reinforce these good habits of collaboration, student always, confidence, reaching for bigger and more ambitious goals, and much more. However, not all business schools teach the same things and what we learn here will conflict with how other people see business. There will be times where our ethics are called into question and we must make the critical decision.

So where is your moral ground? What are you doing to improve your habits?